I’d dreamt of this conversation for quite some time, but Julia is a remarkably modest person—she kept turning me down, gently but firmly. And finally, there came a reason she couldn’t escape—The Jerusalem Ballet’s first tour in America. Under that pretext, I managed to persuade her at last.

You can’t help but fall in love with Julia Shachal, the general director of The Jerusalem Ballet, from the very first moment. Her title suggests discipline, decisiveness, a mind trained for strategy. Yet within her, the CEO and the ballerina coexist in perfect choreography—perhaps dancing their own quiet pas de deux. Firmness and tenderness move in unison, attuned to the rhythm of when to support and when to let go. It feels as though her position has become, above all, a form of care—for people, for ballet, for that delicate balance between art and reality.

Charismatic, with a figure that still carries the memory of the stage, Julia has an extraordinary background and the rare ability to be entirely genuine. She’s also a fascinating conversationalist—a talk with her always leaves the aftertaste of clarity, as if your thoughts have been quietly washed clean.

When Julia speaks about ballet, there’s an undertone in her voice—something like the sound of the sea. Perhaps because it has always been there in her life: from Baku, where she was born, to the coastal cities of Israel, where she now surfs (yes, really!). A few more lines from her biography: a graduate of the Baku Choreographic School, Julia went from soloist of the Azerbaijan State Opera and Ballet Theatre to a dancer with The Israel Ballet, and later became general director of The Jerusalem Ballet, led by Nadya Timofeyeva. Today she is preparing the company for their upcoming tour in Florida—with the same precision she once brought to rehearsing her variation from Don Quixote.

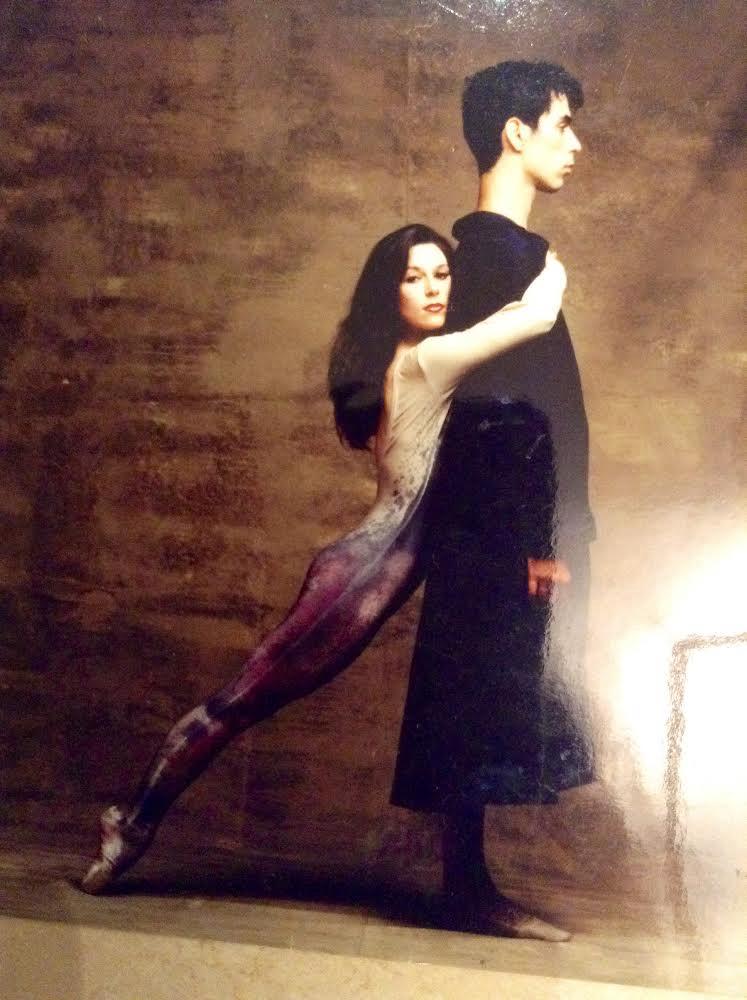

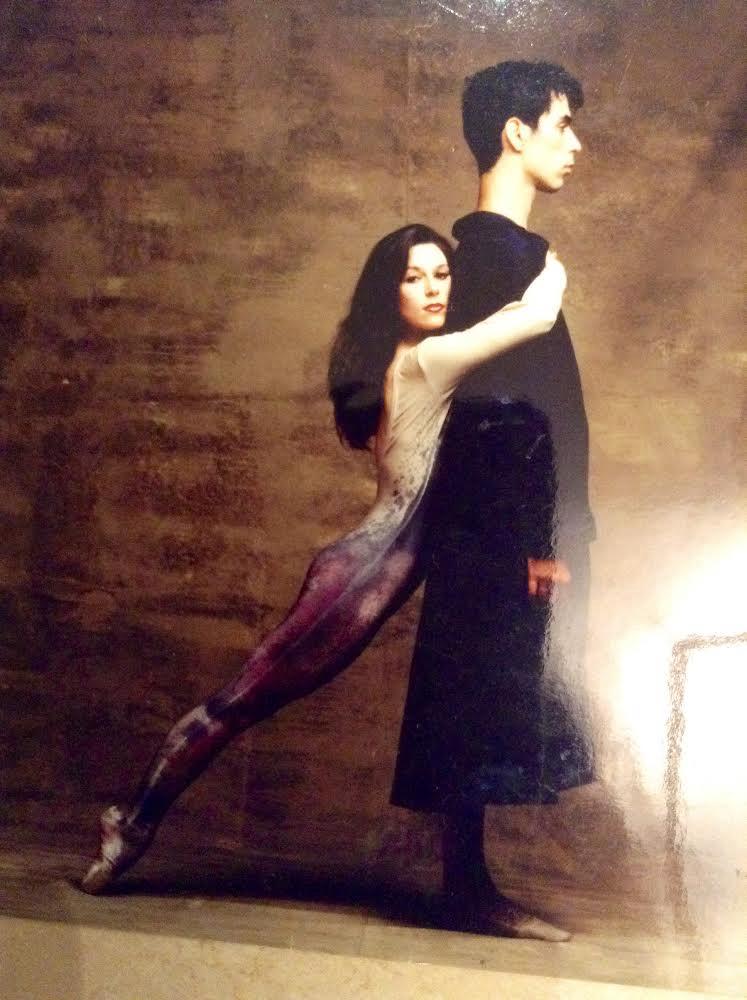

Julia Shachal, Martin Schonberg and Nadya Timofeyeva

– Julia, logically speaking, we should probably start with the upcoming tour—but we’re not exactly formal people, are we? So tell me, is the director of a ballet company more of a conductor, a stage director, a navigator, or a gardener?

– I suppose I’m more of a navigator. The gardener is Nadya—absolutely, one hundred percent. She knows exactly whom to “water,” (laughs) whom to trim, and whom to let grow freely.

– Let’s keep imagining. If The Jerusalem Ballet were a celestial body, would it be a planet, a comet, or a satellite?

– At this stage, we’re probably still a satellite. But I dream of becoming a planet—independent, distinctive, unlike any other.

– And if The Jerusalem Ballet were a person—would it be a reserved philosopher, a rebellious teenager, or a clever adventurer?

– Right now, I think it’s an inventive adventurer. But with time, I hope it’ll grow into a philosopher. When the company was founded in 2008 by two extraordinary women—Nadya Timofeyeva and Marina Neeman—it was, frankly, an adventure. No capital, no funding… They sewed the costumes themselves, built the sets with their own hands. Everything rested on sheer enthusiasm and creativity — and in a way, it still does.

– I actually think adventurism is a wonderful trait. Everyone in the arts needs a bit of that.

– I agree. Adventurism is one of the faces of talent.

– Do you ever have to hold back your own sense of adventure?

– Oh yes. I tend to keep within boundaries—and often end up pulling Nadya back into them too. She’s passionate, spontaneous, wants everything at once.

– What word would you write on the curtain of your theater, if that word were to become the company’s manifesto?

– There’s a word in Hebrew that fits perfectly: tnufa—or be-tnufa, which means “ascent,” “lift,” “upward motion.” It’s a sense of momentum, of rising. I even named one of our school’s programs Be-Tnufa.

– In ballet, there’s always an axis of rotation—a pirouette, a center of gravity, a point of balance. Where is your personal axis, in work and in life?

– My core is compassion, or maybe the inability to be indifferent. In Hebrew, the word is ichpatiyut. And there’s another phrase that echoes in me: my father always told me, and later my sons as well—“only forward.” It became a kind of family motto.

– Ballet demands absolute precision. Where do you allow yourself inaccuracy, chaos, randomness?

– Nowhere. Not in life, not in work. Because eventually I’ll have to deal with it myself.

– Is that a result of ballet training or something innate?

– Both. As a child, I was deeply influenced by my grandmother—she had an incredible passion for order. She taught me that, too. Even now, if I’m surrounded by chaos, I start to panic. So precision and clarity are, for me, a way of life.

– Your grandmother wasn’t a ballerina, was she?

– No, she was a music teacher. She played the piano beautifully, worked in kindergartens, and had boundless energy and imagination. I always felt she had not twenty-four, but forty-eight hours in a day. There were seven of us living together, and she somehow carried the entire household on her shoulders. She wouldn’t let anyone near the kitchen—not even to wash the dishes. And yet, she never missed a single premiere—theater, film, it didn’t matter. She read all the new books and magazines—Novy Mir, Neva—as soon as they came out. She managed everything, and even sewed for all of us. And the celebrations she threw! On my birthday, the neighbors would line up to join. She was truly one of a kind.

– Who in your family decided you should become a ballerina?

– My mother. She said, “You’re a girl—you should have a beautiful figure, posture, grace.” She sent me to the Palace of Pioneers, and later our whole group went to audition for the Choreographic School. I was the only one accepted. My mother got scared—she thought maybe it was a mistake, since we had no dancers in the family. She said, “What if they took you by accident? What if you’re not talented at all?” So she decided to ask a professional opinion. Her friend had a friend, Misha Gavrikov, a dancer at our Opera and Ballet Theatre. They arranged for him to see me and give his verdict. He said, “She’s got potential, though not the kind that makes you faint from awe. Let’s do this: if she scores higher than a C in her first term, let her stay.” I got a B—and stayed. And from then on, never less than a B—and an A at my final exam.

– After school, you went straight to the theater?

– Yes, to the Azerbaijan State Opera and Ballet Theatre. Only four of us from the graduating class were accepted. I danced there until I immigrated to Israel, they gave me wonderful solo roles. At the same time, I studied remotely at the Pyatigorsk Institute of Foreign Languages, majoring in French. That was my mother’s idea too—she worried that something might happen to me, to my legs, and I wouldn’t be able to dance, so she insisted on a second profession. She even hired a French tutor for me when I was in fourth grade. Balancing work and study was tough, but in the end, I earned a degree in teaching French—and even taught for a year at the ballet school.

– Did French come in handy in Israel?

– Oh, very much so! When I first arrived, I spoke only French with the Moroccan community in Ashdod.

– When did you start dancing here?

– I immigrated when I was four months pregnant, expecting my first son. As soon as I gave birth, I went to audition for Berta Yampolsky at The Israel Ballet—and she accepted me immediately. Of course, I had to get back into shape, so I trained from morning till night, but I was happy—absolutely happy. I felt at home, no longer a “new immigrant.” That heavy feeling of displacement disappeared at once. I danced many beautiful roles—especially Balanchine’s works, which were so precious to us at the time. The Israel Ballet had permission to perform his choreography, and coaches from the Balanchine Trust would come to work with us. It was an invaluable experience. I remember, in the late ’90s, dancers from the Bolshoi came to perform here, and they told us, “If you’re dancing Balanchine—you’re already blessed.” I was lucky to dance the lyrical second movement of Symphony in C by Bizet–Balanchine—a solo like a white adagio from Swan Lake. Later, Berta Yampolsky choreographed several ballets for me, including Gurre-Lieder to Schoenberg’s music. There were many solos, and the movement vocabulary was entirely different.

– Does your body feel closer to classical ballet?

– Absolutely classical. My body doesn’t know contemporary ballet very well, which I regret. There was a period when Ido Tadmor became artistic director at The Israel Ballet, and I decided to attend contemporary ballet classes for adults to get a feel for his style. I really love that movement vocabulary, but it’s hard to channel it through my own body.

– It’s hard to believe that someone so slender and graceful has three sons. People must wonder how a ballerina recovers after childbirth.

– With difficulty! Each pregnancy I gained about twenty kilos. When I was pregnant with my second son, I kept dancing. But after his birth, I realized returning my body to stage shape would be too hard. I was thirty-four, and our company was young. I decided it wasn’t worth fighting for another year or two on stage.

– What’s the most absurd but somehow brilliant offer you’ve received in your career?

– Actually, while I was pregnant, the general director of The Israel Ballet, Hillel Markman, suddenly said: “Come help me in the marketing office.” Later, after I gave birth and was preparing to leave the company, he stopped me: “You’ve started promoting the ballet so well—stay.” That’s how I transitioned from soloist to sales manager. Gradually, I became marketing director, then advisor to the general director—handling both sales and creative promotion. That shift was decisive: it allowed me to combine my experience as a ballerina with producer logic. I also brought many dancers from abroad into the company, insisted on including Giselle and Don Quixote in the repertoire—classics still performed today. It wasn’t easy, but I managed to convince Berta.

– So you stayed with ballet, just in a different role.

– Exactly. That “absurdity” became my happiness. Experience, contacts, understanding—everything came together. Later I worked as an independent consultant in marketing and production. All of this I now bring to The Jerusalem Ballet.

– You mentioned that you’re constantly learning.

– Yes, it’s both my weakness and my joy. I completed a course on “Management of Cultural Institutions” at Tel Aviv University, and recently the manhigut be-tarbut program—“Leadership in Culture.” It was remarkable: the professors didn’t lecture us, they listened. Essentially, we learned from each other—directors from various cultural institutions.

– Does being a ballerina as a general director help or hinder?

– Both. As a professional, I see everything I’d like to do differently or improve, but I can’t always act on it because I’m not a teacher or choreographer. Someone from outside might find it easier—they see less detail. I notice everything—for example, if the girls don’t extend their fingers properly.

– How would you define the artistic mission of The Jerusalem Ballet today? What’s at the core of its identity?

– It’s simple: when we say “The Jerusalem Ballet,” we mean Nadya Timofeyeva. She is the heart, the axis, the inspiration of this company and school. Mother, teacher, choreographer, director, artist—she never gives up and nurtures the next generation of dancers with love and faith. Without her, this ballet would never exist. I am in awe of everything she has done and continues to do, often under very challenging circumstances. As for the mission of The Jerusalem Ballet, try raising students who progress from school to stage, remain in the art form, and dance in our company! And in many other companies worldwide—Nadya’s students are everywhere, including Israel’s finest, like Batsheva, Kamea, Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company… At one point, half of The Israel Ballet consisted of her students.

– What would be the “ideal repertoire portrait” of the company ten years from now?

– Classical and neoclassical—or, as it’s often called now, contemporary classical ballet. But I also want our dancers to perform modern dance equally well. Real, profound, not decorative.

– Are there leading companies in the world that you look to as benchmarks?

– Essentially, all of them. The Grand Opera, Dutch National Ballet, Royal Ballet, Bolshoi, Mariinsky—they all perform both classical and modern works. At the Grand Opera, for instance, Hofesh Shechter’s pieces—pure modernism — are in the repertoire. There’s also Ohad Naharin’s work—also pure contemporary. Those companies set a standard, and of course, everyone follows them. Recently, in summer 2023, I was impressed by NDM Ballet Ostrava from Moravia and Silesia, with whom I worked alongside Ofer Zaks. They’re astonishing, still relatively unknown, but their repertoire is incredible: classical, contemporary classical, and contemporary. They danced works by Mauro Bigonzetti, whom I adore and hope to work with one day. If in two years The Jerusalem Ballet becomes that kind of company—with its own repertoire, narrative works, and versatility across styles—I’ll be happy. For me, The Jerusalem Ballet is a ballet theater, not just a company—and that distinction matters.

– You’re about to tour Florida with two productions—Houdini: The Other Side and Memento. What, in your view, will surprise American audiences the most about Israeli dancers—something not obvious from the posters?

– I think it will be their artistry. Western companies are generally less emotionally expressive, but Nadya Timofeyeva’s ballets can’t exist without emotion. The performers’ expressiveness is what will astonish the most. In Memento, for instance, which tells the story of ballerina Franziska Mann, who danced in Auschwitz’s gas chamber and shot three Nazis—the emotional intensity is palpable. It’s impossible not to live through it from the inside. Sometimes dancers even start crying. They say a performer shouldn’t cry—should make the audience cry—but the feelings are overwhelming, sometimes barely allowing them to breathe… and that transfers to the audience. Recently, at a performance in Bat Yam, everyone cried—dancers and spectators alike.

– I’ve only ever seen that once, at a live performance of La Bohème with the Israel Philharmonic. Real tears flowed from every singer, Mimi’s makeup even ran… And at the finale, the audience cried too, as if experiencing her death for the first time.

– It’s hard to imagine singing and crying simultaneously. Dancing and crying is probably easier… But when it happens, it gives you goosebumps. Especially in Memento, where both theme and time are in perfect alignment.

– This tour to Florida is a significant step. Beyond performing on a new stage, what are the strategic goals?

– This is more than a tour. It’s a real collaboration with Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. Alongside six performances, we have masterclasses by Nadya Timofeyeva and Martin Schonberg, her right-hand and deputy artistic director of The Jerusalem Ballet. Nadya is preparing a special piece for the students—they have just a few days to learn it and perform it before one of our shows. Additionally, two students will participate in Memento itself—as characters. A girl will dance a flower girl, a boy will be a postman delivering terrible news to a Jewish family in Poland, and also dance as Franziska’s younger sister’s friend. It’s very moving to me. Nadya and Martin are currently rehearsing via Zoom, and their American teacher, Aidan Nettles, is rehearsing fragments on site. She wrote that the students are now working on Atikva. Interestingly, neither student is Jewish, and Aiden herself is African American.

– She heads the choreography department?

– Yes, the department of choreography and dance. They have some classical training, but mostly modern and jazz. So this is a real challenge. Next year, these students will come to Jerusalem for a summer course. This isn’t a one-off tour—it’s a long-term collaboration.

– By the way, why Florida for your first tour?

– These tours became possible thanks to the chair of our amuta, Dr. Ayelet Giladi—everything starts with personal connections, and she has many in the academic world, since her life has always been intertwined with education. It was Ayelet who introduced us to Professor Aidan Nettles at Florida Atlantic University, whom I mentioned earlier. She suggested that The Jerusalem Ballet present our shows remotely, and she was thrilled… and that’s how it all happened.

– Are there concerns about anti-Israel sentiments in Florida?

– The Americans are prepared for anything; local police and campus security will ensure our safety. Although Boca Raton is home to many elderly Jewish residents, it’s welcoming and friendly.

– If you could send the American audience one feeling in an envelope, what would it be?

– Emotion. Experience. Art—especially dance—must be emotional. It has to move people, convey feeling. You can make beautiful images, but if they’re indifferent and cold, they mean nothing. I am a deeply emotional person myself, and I believe that what remains after a performance are the feelings.

– Which moment of the tour are you most looking forward to, not as a director, but as a human—almost childlike?

– Of course, I look forward to the first applause. When it turns into ovations and shouts of “Bravo!” I hope that’s what will happen.

– Is there something missing in your work?

– Probably confidence. I’m no longer the shy, reserved person I once was, but back then, I was terribly inhibited. On stage, movement freed me, especially. When I arrived in Israel, even my parents noticed more freedom in my movement.

– Could it be the country’s spirit of freedom that influenced you?

– Perhaps. When I joined The Israel Ballet, there were many European and Israeli dancers. Their style, their freedom—it all rubbed off on me, I think.

– Let’s turn to your favorite activity—surfing. What do ballet and riding a wave have in common?

– Beyond balance, coordination is key on the board. I think it’s just as crucial in managing a company and in ballet—everything has to be synchronized.

– If one classical ballet variation were performed on a surfboard, which would you choose?

– The sea makes me think of Le Corsaire. Pirates, a ship… I’d pick a variation from there and perform it on a board.

– Is there choreography in the ocean?

– Absolutely. I can watch the sea endlessly as if it’s infinitely beautiful choreography. I see it more as contemporary movement than classical, actually.

– Sometimes the waves, those little whitecaps, remind you of tutus, right?

– Yes, sometimes. But the motion is more like contemporary dance than classical.

– What’s your inner “soundtrack” while surfing?

– You might be disappointed, it’s not classical music. I sing Magomaev’s Blue Eternity. When paddling long distances, I hum it constantly. I speak to the sea through that song.

Photo by Gili Lifshitz

– Surfing requires overcoming fear. What helps you in those moments?

– When a wave rises, intuition and coordination are everything. Timing is everything: if the wave, your paddle, and your entry aren’t in sync, you won’t catch it.

– Does ballet help you surf?

– Sometimes yes, sometimes no. In ballet, we learn to balance on straight legs—with bent legs, nothing works. But in surfing, my instructor constantly tells me: bend your knees, or you’ll fall! I had to retrain myself. Lower stance equals stability, and when standing, knees should be slightly bent. I’m used to it now, but at first it was very tricky.

– Surfing is about overcoming—fears, doubts, yourself.

– Exactly. For me, calm waters are pleasure, but waves are real challenge—fear and joy at once. I’ve mostly conquered the fear, but catching the right wave is still a test. The sea is always different; today I may ride a certain height, tomorrow I might not. Luckily, my mentor Carmit knows the sea like the back of her hand and teaches me to feel the wind, trajectory, gaze—everything matters. She’s a true dancer on the board.

– Speaking of which, are there similarities between surfing and ballet?

– Balance, fluidity, presence, coordination — all crucial in both. Even virtuosos fall sometimes. I didn’t surf for a while after a bad fall that twisted my knee. In my ballet career, I had just one serious injury—when my partner dropped me during rehearsal. We were preparing Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss, choreographed by the incomparable Rudy van Danzig from the Dutch National Ballet. Four couples and one soloist — the Angel of Death — danced four duets, insanely difficult. I was in the third, the hardest. My partner dropped me unexpectedly — I thought I was still in the air… I injured my foot. Everyone predicted I’d be out for months, but I was back on pointe in two weeks.

– Besides surfing, do you have another vivid hobby?

– I love yoga. Truly. I try to practice often because it develops strength, flexibility, and coordination.

Photo by Gili Lifshitz

– Today’s ballet artist is not just a performer, but a bearer of a certain cultural code. What qualities must a dancer of The Jerusalem Ballet possess? Are there distinctive traits that make them recognizable as a product of Nadya’s school?

– Pirouettes. Nadya’s school is all about pirouettes. Every student of hers spins beautifully—she teaches it masterfully. And Martin brought elements of the European school into our company—the culture of the foot, turnout, refinement. Our lead ballerinas now have very well-trained feet. I always pay attention to the feet and hands—that’s the highest craft in ballet. Of course, nature plays a role—some feet are difficult even for Martin to retrain—but good choreography produces stunning results.

– How does The Jerusalem Ballet balance preserving Israeli identity while staying open to global trends?

– Israeli identity is indeed an interesting topic. Our productions are built on a synthesis of European and Russian schools—and that’s wonderful. But what is “Israeli-ness” in classical ballet, where the country’s traditions are minimal? Nadya chose Jewish and Israeli themes, that’s the main focus of our productions. She develops them through dance, drawing on literature—for example, Moshe Shamir (remember our ballet He Walked the Fields) and other Israeli classics. I’d call it a kind of ballet-ization of local novels. Abroad, it’s received more as Jewish themes than specifically Israeli, but that’s our niche: telling Jewish stories through dance. Martin has embraced this as well; he resonates with Kafka, for instance. Recently, we premiered Kookl@, about a girl who lost her doll and to whom Kafka wrote imaginary letters. In this sense, we are pioneers—it’s always exciting to create something truly our own.

– What does “speaking the language of ballet” mean today, in a world dominated by visual and digital forms?

– First, dance is a universal language—it erases borders. And second, in my view, ballet theatre should be a messenger of culture, conveying feelings and bringing people together. And I don’t say this lightly. A few weeks ago, we went to Sardinia with a group of surfers and worried how we’d be received, knowing we were Israeli. Sitting in a small street-side restaurant, a musician starts playing songs from our youth—Felicità, Cantare… All the Israelis, mostly women, jumped up, started dancing and singing. And everyone else in the restaurant joined in—dancing, hugging, rejoicing together. Nobody cared who we were or where we came from. That’s the power of dance. And if dance tells a story, like in The Jerusalem Ballet, its value is undeniable.

Julia with hasband, Yaron Shachal

– If you could give advice to a young ballerina just starting this demanding path, what would it be?

– Dance all the time. Give yourself completely to it, while you have the strength and the jump. Ballet is youth. Experience comes, the jump fades—as Plisetskaya said. While you’re young, while you can jump, make the most of it.

– And what would you say to your eighteen-year-old self?

– “You have no idea how many waves lie ahead. Just don’t be afraid to dive in.”

Photos courtesy of Julia Shahal / personal archive |